Joseph Muscat and Konrad Mizzi stoke up another Dalli scandal

Casting about for something to use in their now-standard diversionary tactic of trying to distract people from growing government scandals by pulling a ‘skandlu PN’ out of their hat, Konrad Mizzi and Joseph Muscat have added unwittingly to John Dalli’s escalating problems by stoking up the old embers of yet another corruption case – which he won’t want people to remember or, if they are fresh to the news, to find out about.

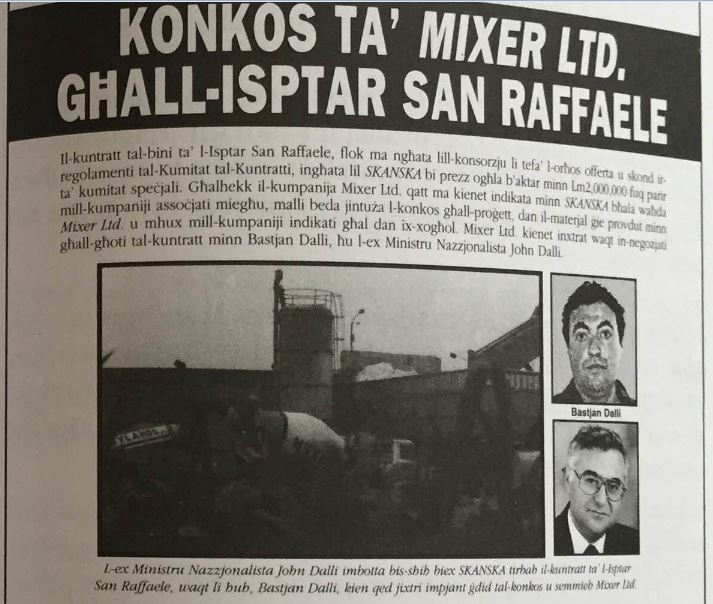

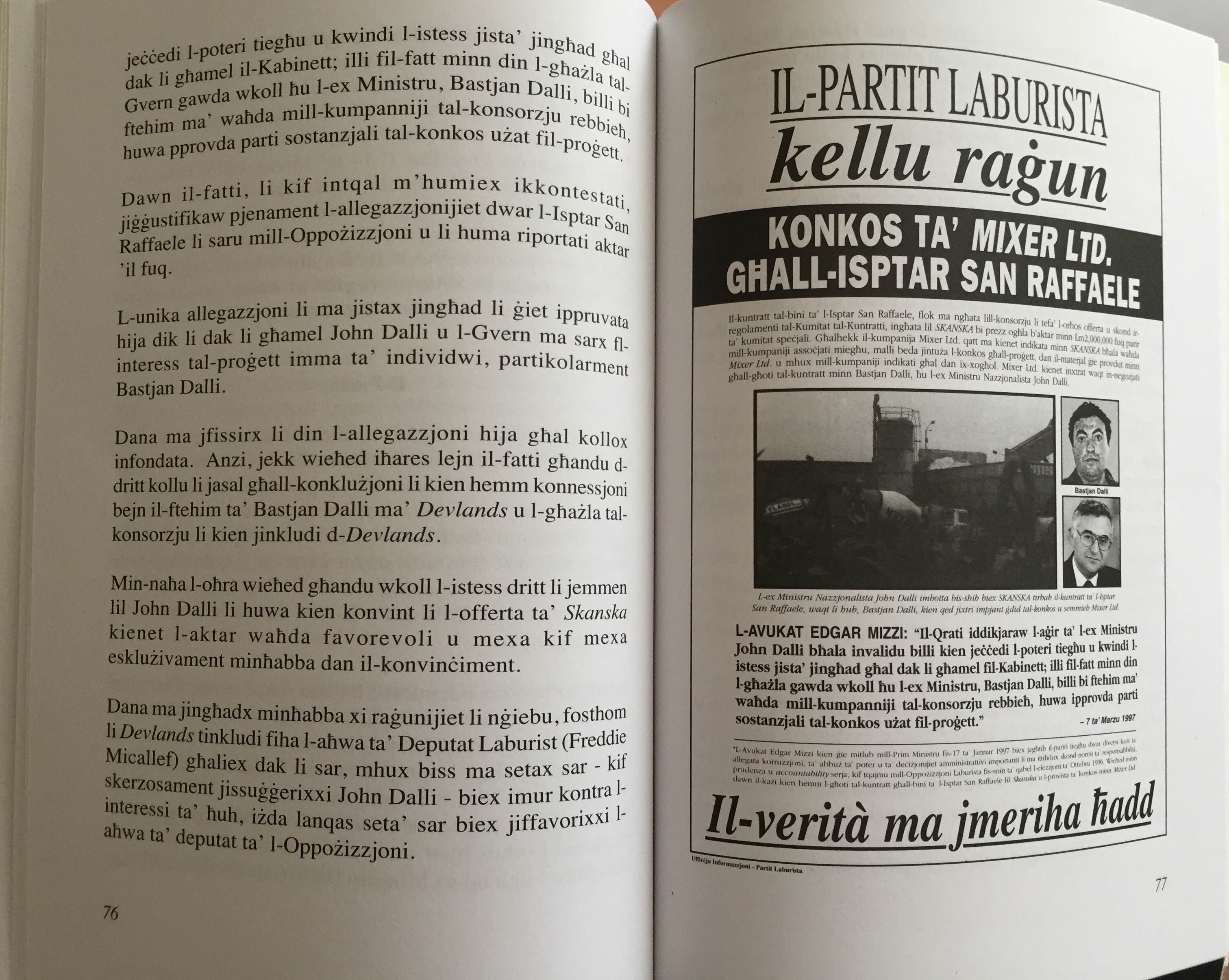

By serving up their shock-horror report on how the poor quality concrete at the state hospital will cost a fortune to set right, all they have done is prompt the press to remember that the concrete was supplied by drug-trafficker and Camorra fixer Bastjan Dalli in corrupt collusion with his now disgraced brother John, who was finance minister at the time.

John Dalli has for the last few years been in highly suspect collusion with Joseph Muscat, and while he was European Commissioner even sank as low – in violation of European Commission regulations – as to use his frequent appearances on the Labour Party’s television station to promote the power stations manufactured by a client of his company, John Dalli & Associates. That client was Sargas.

The 1990s were a while back, and in those days the newspapers did not have internet news portals – so an internet search won’t give you anything. Fortunately, to save journalists from trawling through their own print archives in the office and at the National Library, there exists a very convenient book – called L-Iskandli tal-PN” – published by the Malta Labour Party’s Information Office in 1998 as a campaign tactic for the general election which they lost that year.

(No number of Dalli scandals were, apparently, enough to persuade people they should give themselves another five years of Alfred Sant and his rubbish cabinet.)

L-Iskandli Tal-PN is based on the report of an inquiry conducted by former attorney-general Edgar Mizzi at the request of Prime Minister Sant.

I have uploaded photographs of the relevant pages of the book, which you can enlarge and read – but for those of you who are in a hurry, or who don’t understand Maltese, the crucial points are below.

1. In 1994, the Nationalist government put out a call for tender offers for the construction of the new state hospital, which was then still being called San Raffaele.

2. Several offers were received, including two with different prices from the Skanska/Devlands/Blokrete consortium.

3. John Dalli, who was finance minister and whose ministry was responsible for tender offers, pushed hard for the the Skanska/Devlands/Blokrete consortium to get the tender. The tender adjudication board decided in favour of another consortium, CMC. John Dalli set up a special tender evaluation committee, which over-ruled the tender adjudication board’s decision, though it had no power to do so at law.

4. The consortium preferred by the tender adjudication board took the government to court, which issued a warrant of injunction preventing the government from proceeding with the tender until the case was heard.

5. A tangle of legal proceedings followed, during which the suing consortium failed to respond to part of the procedure within the time frame stipulated by law. The case fell through and the Finance Ministry proceeded to award the tender to the consortium favoured by the finance minister (John Dalli).

6. Meanwhile, the finance minister’s brother, Sebastian aka Bastjan – a drug-trafficker, whisky smuggler and Malta fixer for a Naples Camorra family, who took care of many of John Dalli’s business interests in Gaddafi’s Libya when Dalli’s daughters were still too young to do so themselves – was busy buying a concrete batching plant.

7. (This bit is not in the book but I know it from other sources.) The concrete batching plant was owned by a company called Planka Ltd. Sebastian Dalli bought it from Joe Gaffarena, who had run it for years on a large site that had no planning permission. Because it had no planning permission for the 40-tumolo site, Sebastian Dalli bought it at a good price. It hadn’t been operating for years because of trouble with that planning permission and financial woes. Unbeknown to Joe Gaffarena, planning permission was (miraculously) approved the day before he and Sebastian Dalli signed the contract. Gaffarena sued Dalli for a very large amount. I have no information on how that case ended up.

8. Sebastian Dalli changed the company name to Mixer Ltd. Mixer Ltd was not part of the consortium which won the hospital construction tender, but as soon as construction started, it began supplying the concrete. At first, it did so covertly, and didn’t send its own concrete-mixers to the site. Devlands concrete mixers used to go to Mixer Ltd’s batching plant, load up on concrete, and drive to the construction site. But then Sebastian Dalli (and his brother the finance minister) grew more brazen and defiant about it and Mixer Ltd’s own concrete mixers delivered the concrete directly to the construction site.

9. My note: Devlands Ltd was at the time owned by the brothers of the late Labour minister Freddie Micallef, who formed part of the cabinets of Dom Mintoff and Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici. Jason Micallef’s father was another brother.

9. Mixer Ltd was not the only supplier of concrete, but in 1996 alone, it supplied a third of the concrete used in the construction.

10. Sebastian Dalli released a statement that year saying that he had bought the concrete batching plant because he knew for a fact that he would be supplying the concrete for the hospital construction. He said that during the tender offer period, he had reached agreement with Devlands on this, but he had also agreed with G V Xuereb, which was part of the rival consortium that ended up taking the matter to court. (So he and his brother the finance minister had all their bases covered.) When George Xuereb was asked during the inquiry whether this was true, he replied enigmatically that “charity begins at home”

11. Neither the Skanska/Devlands/Blokrete consortium nor the G V Xuereb/CMC consortium needed the third-party concrete-batching services of Mixer Ltd. Skanska had its own batching plant in Malta. Blokrete – as the name implies – had been making concrete and supplying it to Malta’s building industry for around 30 years, and even bought another batching plant to service the project. CMC, the other consortium, had bought the Five Star batching plant.

12. This is not in the book but is my own note. John Dalli concealed from his prime minister (Eddie Fenech Adami at the time) and fellow members of the cabinet that his brother Sebastian had bought a concrete batching plant with a view to supplying the concrete for the hospital construction. He especially concealed the fact that his brother had done so because he had received a commitment that the concrete would be bought from him, even before the tender process had begun. For the first few months of 1996, the concrete was supplied covertly. By the time Mixer Ltd was supplying it openly, Malta was heading for a general election. In October 1996, there was a change of government and Alfred Sant became prime minister. After October 1996, Mixer Ltd was supplying concrete to the hospital construction site under the Labour government.

13. Edgar Mizzi’s inquiry – set up under the incoming Sant government – found that there was no evidence of any wrong-doing “whether you believe John Dalli or not”, so there was no reason to set up a formal investigation as there were no new facts to be discovered. Sebastian Dalli carried on supplying concrete for the hospital construction.

14. Of course, in the very different cultural climate of today, we know that this was not about criminality or trying to prove that John Dalli pushed X or Y so that ‘his brother’ would get the business, but about immorality in politics and lack of transparency. The way it looks, and the well-founded suspicion that the finance minister’s brother, with or without the finance minister taking a cut too, had found a way to make money off the construction of the hospital would have been enough to stop it.