Ship repair – it’s not pastizzi and fenek

The prime minister said in parliament a few days ago that listening to the Opposition talk about the drydocks is a surreal experience, because the Opposition sounds as though it lives in another world.

He spoke as the House prepared to vote on the transfer of Malta’s ship repair facilities to the Italian company Palumbo.

Even as Greece collapses, he said, those facing him on the other side tried to justify what happened with the drydocks over the years.

What happened was this: the country carried the drydocks for so long, and to the tune of so many hundreds of millions, that it is the single greatest example of throwing good money after bad in the history of our economy, and by a long, long shot. It is Malta’s Billion Lira Disaster.

The dockyard was never intended to be a commercial enterprise, and it was not planned as such. The Royal Navy needed ship repair facilities in the Mediterranean and this was the place to put them. If something went wrong in the Middle Sea, it was a lot easier to sail into Grand Harbour than it was to sail to Portsmouth.

The yard wasn’t conceived as a money-making venture but as the equivalent of an on-the-premises mechanics’ workshop in a car hire company. It was the Royal Navy Dockyard, Malta. In the days before labour laws, people were hired and fired as needed. A ship came limping in, a call went out for labourers and skilled tradesmen, they did the job, got paid in pennies or shillings, the ship sailed out and the labourers and skilled tradesmen went on their way to look for other work.

This is a much simplified version of how things were, but you get the picture.

When Britain’s lease on its military base here expired at midnight on 31 March 1979 (which would make Jum il-Helsien April Fool’s Day), the greatest fear was that the dockyard would have to be shut down because it had become redundant. Its main purpose was no more.

Dom Mintoff had built up the departure of the British navy into a great political event. He didn’t tell his followers that Britain’s lease had expired and that they weren’t renewing. He told them that he had kicked the British out – and his supporters, most of whom were illiterate or otherwise ignorant at the time (never forget how new Malta is to literacy) believed him utterly.

Because he had sold to the masses the departure of the British navy as his personal achievement, Mintoff was especially keen that there be no negative consequences, but only massively positive ones. Catastrophic economic consequences were particularly undesirable. He didn’t have a game-plan for economic restructuring which would mop up the resulting unemployment, the main fear rippling through the country.

Mintoff’s supporters may have hated the British on political principle but loved them in person, and it can be said safely that nobody loved a sailor as much as the people of Mintoff’s home town and the core base of the Labour Party’s support. They jammed the bastions on 31 March 1979, weeping copiously as the last ship sailed out, shouting ‘Goodbye, we love you!’ and waving madly. The navy kept shops, bars, and jobbing workmen afloat, and that is quite apart from the fact that there were many romances indeed.

It was easy to say ‘I kicked out the British’ but a lot more difficult to come up with a plan for the dockyard. People in Malta in those days, like the Greeks until their economy cracked, thought that the government and is-sinjuri had an unending supply of money which recreated itself indefinitely.

The sinjuri – and heaven knows there were few of them back them – could be taxed and Mintoff is-Salvatur ta’ Malta could dig into his kaxxa and pay dockyard workers for the remainder of eternity even if they sat about doing nothing for most of the time and never went into profit or broke even.

And yes, that’s what happened. Mintoff could not sell the departure of the British as an unqualified success and personal achievement to go down in history if he also had to run down the dockyard and then close it completely. So Malta’s back was almost broken over the years by carrying this terrible burden.

With such a large workforce, and using systems designed for a naval yard and not for a commercial one dealing with merchant ships and private yachts, the dockyard could never make money – no matter how productive it was and how many ships came in. It was impossible, doomed to failure from the start.

It is a failure that has been protracted tortuously over 30 long years – three decades during which money has been siphoned from the taxpayer, money that could have been spent instead on development and investment, so many millions that they can no longer really be counted.

On early retirement schemes alone, to hive workers off and make the yard saleable, the government has spent €50 million. Two thousand men took advantage of the schemes and left the yard’s employment, but 1,300 have been left on the payroll and it should be 700.

In the eight years between April Fool’s Day, 1979 and the departure at last of the damnably miserable Labour government, there was never any money for schools, for tertiary education, for reverse osmosis plants, for telephony or for a power station, but there was always money for the dockyard.

Even after the dockyard workers had welcomed the new government by going on the rampage in Valletta, that new government thought it best to keep things going, trying to restructure, trying to find business, trying to do this and that – don’t rock the blessed boat.

Eddie Fenech Adami was many things, but he was no Margaret Thatcher and he wasn’t going to take on the union or the dockyard. Instead, he did the next best thing, and revved up the country’s economy so that we all earned more and the burden of carrying that sack of rocks would not be as great, in relative terms, as it had been before. And there was money for other things after the yard workers’ cheques had been drawn.

At one point in recent years, the dockyard had an accumulated debt of Lm300 million (around €700 million). The government decided to absorb this debt, which raised Malta’s deficit to 10%.

Now the prime minister has said in parliament how deeply he regrets the fact that some decisions about the dockyard were not taken earlier, when the international economic situation was better. The European Union, when we joined, had agreed that state aid to the dockyard would be permitted for seven years but no more.

Those seven years are almost up, and given that the yard still hasn’t struggled to its feet and has no hope of doing so in so short a time, it had to be sold and the best of luck wished to any buyer who could be found, given that the market for European shipyards isn’t burgeoning. The government first thought it might negotiate for an extension of the permissible period for state aid, then decided to do what should have been done in 1979, and lance the wound.

A buyer was found and the Opposition, of course, objected – first because the yard was being sold at all, and then because of the price at which the deal was struck. One was tempted to say, look, if you’re so damned keen, pool your resources with Tony Zarb and buy it yourselves.

Joseph Muscat even went so far as to say that the government is selling the dockyard as an act of vengeance on the Labour Party. But Muscat and his men ignore the fact that had a buyer not been found, the prospects would have been far worse. With no state aid, the dockyard would have to be declared bankrupt and 1,300 men would lose their jobs overnight, with no plan of action to suck them into alternative employment.

There was an international call for tender offers for the purchase of the yard, overseen by the European Commission, which specified that the scope of activities of the yard could not be restricted to ship repair but must cover the wider ‘maritime activities’. So ship repair may yet cease altogether.

The Labour Party is hysterical at the thought. Perhaps it imagines that ship repair is like pastizzi and fenek – a local tradition which has to be preserved at all costs, the difference being that there’s a market for the first two.

The Labour Party, unable even to organise the proverbial in a brewery, seeks to convince that it would have done things better, not sold the yard at all, kept those people on, somehow made money and failing that, kept the place as a sort of shrine to ship repair, pulling money out of the national health budget and education to fund it.

Given that the Labour Party is the original source of the problem, I think it should be told in no uncertain terms to sit down and keep quiet. Do you really want Anglu Farrugia’s advice on the shipyard? I don’t think so – though he might yet discover some stolen Labour votes hidden in a welding station.

This article is published in The Malta Independent on Sunday, today.

14 Comments Comment

Leave a Comment

Great article. A concise history of a Maltese tragedy.

Frankly I really get a feeling that the Privatisation Unit does not have people with too much commercial sense. I would say common sense.

It is indeed unfortunate that privatisation of the shipyards came two years too late, because there would probably have been a couple of bidders from the the big players.

I have a gut feeling that the Palumbo project will fail, as they are indeed a small player. Unfortunately, this silly tendering system puts the government in a straitjacket.

Were there any attempts to get some interest from South Korean or some other Asian yards?

Even if attempts were made and failed, the logical way forward was to grant a smaller concession (at a lower rental) to Palumbo, say two docks, and certainly excluding the massive Red China Dock. This way it keeps the shipyards and respective trades operational, and at the same time keeping options open for another operator for the remaining docks when the shipping market picks up.

The unit correctly did not award the yacht repair facility and the Marsa yard, where the offers were very low.

Again I have serious reservations why the Manoel Island yacht yard was retained for this purpose. The storage yard is very small for Malta’s requirements. There were possibly two options here. Lease out the slipways only and remove the yard, or remove the whole yacht yard completely and lease out that part of Manoel Island for tourist development plus marina. Such a project would have generated far greater revenue for the government.

The Manoel Island yacht yard facility could have been transferred to a larger site on PART of the Marsa shipbuilding site. Malta will never make commercial sense for shipbuilding but only ship/ yacht repair.

The remaining part of Marsa shipbuilding could have a regeneration plan together with the site of the Marsa power station. Indeed once the power station is shut down and the area cleaned out, this could also be a site for upmarket development plus another private marina.

One has to bear in mind that Malta’s waters are deep and building breakwaters is extremely expensive. Therefore extreme care must be taken to make optimal use of the limited space in grand harbour.

This also brings me to the White Rocks project. Thankfully the sell-off to a budget Spanish operator fell through. The way forward here is to create another golden mile of 5 star hotels.

The government should award one area for a five-star hotel every two years or so, so gradually Malta will increase its 5-star bedstock. Preferably the whole of White Rocks should be a mix of say two or three seafront hotels plus villas.

The permits for these hotels should be for a mix of hotel plus apartments on the higher levels, as is the concept of all new hotel developments. It is incredible that MEPA does not allow such permits in 2010!

The leaders at MEPA are still in a time warp. Indeed I sometimes wonder how could we have good planners at MEPA, if their overseas exposure to new developments is probably very limited or nonexistent.

Finally the government must immediately take back possession of the Verdala hotel , where Mr Anglu Xuereb abandoned this project. Does it makes sense to have a hotel inland in Malta? The building should be demolished, and issue a request for proposals for the site, failing all, just rehabilitate the area.

Another well written article. An accurate account of how the dockyard was manipulated at the expense of the poor Maltese worker.

The upcoming new generation reading about how the Labour Party manipulated their own people are gradually distancing themselves from the GWU and MLP. History will be unkind to Mintoff.

It doesn’t help that his own people are also indifferent about him. This apathy is transcending towards the MLP.

I can’t agree with the LP making such a fuss about the dockyard being sold to a private company. Giving it away for free would still have been a good bargain for the Maltese economy.

and would you enlighten us, how you figured that out, wise Solomon?

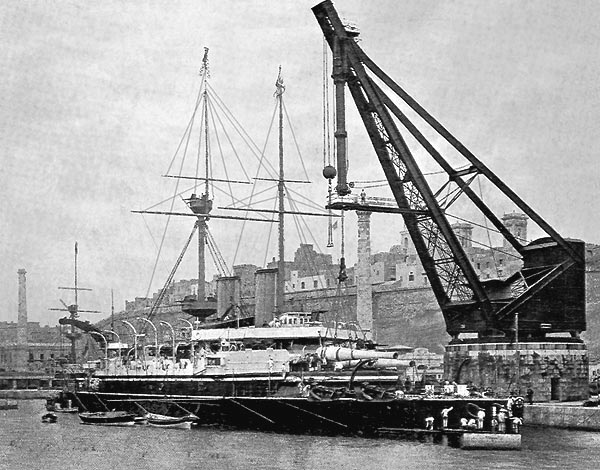

Nice Picture of HMS Camberdown, when the The Dockyard was at it peak. You forgot to mention the role the GWU played at the dockyard. GWU leadership throughout the ages always defended unproductive work practices there from the first strike in 1943 when Malta was at war to when the dry docks were privatized to when it was closed down.

At last, the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth about the largest millstone hanging around our collective necks for the last fifty years and for which we, the taxpayers, had to fork out one billion smackers.

Point of order: For the sake of accuracy, it’s Malta’s Billion Euro Disaster (not billion lira), but otherwise absolutely spot on.

[Daphne – No. That Lm300 million debt was just a fraction of it. It was the debt accumulated at that point. You also have to factor in the annual bail-outs by the government for suppliers’ bills that had to be paid so that supplies could continue to be received, the salaries which were paid out of taxes over 30 years, the opportunity cost, and so on.]

It’s simply frightening to think that Joseph Muscat has the cheek to complain about ‘vengeance’. Any person in his right mind knows that the drydocks should have been shut down long, long ago.

Even more frightening is that tens of thousands will believe him. The sort of tens of thousands that believe that they are owed a home, education, a health service, security and often a cushy job in the civil service or with a state-owned organisation. The parasites that want everything for ‘free’ when ‘free’ means paid for by honest, hard-working people.

Until the PL can make its supporters see that there is no such thing as a free lunch Malta will never be able to realise its potential.

This article is absolutely brilliant! Well done, Daphne!

This was far more interesting than Charlon Gouder’s “dossier” about the dockyards.

The GWU is saddened by the closure of the dockyard, this was their ‘TERRORIST H.Q.’ This was the place where the famous trucks laden with thugs ready for their tour of terror through our Capital City used to be organized.

LEST WE FORGET.

Couldn’t agree more with you here, Daphne. At last a step, a big step in the right direction.

On a lighter note, one thing I didn’t agree with you. You said the Labour Party can’t organise a piss-up in a brewery, but one has to admit that Joseph Muscat alone organised one in Parliament a couple of weeks ago.

This must be one of my favourite articles, and it is also pretty spot-on. I hope that those who do not know this stuff read this article. I’m sick of hearing idiot Labour supporters saying that the drydocks was some sort of magic, money making enterprise, and that the Nationalists ended up ruining it.

“When Britain’s lease on its military base here expired at midnight on 31 March 1979 (which would make Jum il-Helsien April Fool’s Day), the greatest fear was that the dockyard would have to be shut down because it had become redundant. Its main purpose was no more.”

By 1979, I believe the British Navy was not using the Dockyards very much, if at all. British Navy presence in the Mediterranean had been reduced to a minimum by then.

While I agree with the article in essence, I do not think that the closure of the base, per se, affected the volume of work at the Drydocks.

It did not forbid the repair of military vessels. What did severely limit repairs were the 1987 amendments to the Constitution article 1 (3) (e).

[Daphne – The dockyard has been heavily in the red every year since it ceased to be the Royal Navy Dockyard, Valletta. It didn’t make money before that, either, but then there was no bottom-line to look to. It wasn’t – to use current terminology – a cost centre. It was an overhead. The Royal Navy had ships. Those ships needed repair and maintenance. End of.]