UBS whistleblower Bradley Birkenfeld given Malta residency despite criminal record

UBS whistleblower Bradley Birkenfeld, who gave a talk at the Casino Maltese in Valletta last Friday about the whistleblowing deal which netted him $104 million (before tax) from the United States Inland Revenue Service, lives in Malta as a permanent resident, this website has learned.

Birkenfeld was jailed for three years and four months in the United States for conspiring with the mega-rich Russian-born and California-based real estate developer, Igor Olenicoff, to evade US income taxes. Olenicoff reached a settlement with the US government in which he paid $52 million in back taxes, fines and penalties, agreed to repatriate all his funds, and escaped prosecution.

During his trial, Birkenfeld admitted that he had once bought diamonds with Olenicoff’s illicit money in Europe and then smuggled them across the Atlantic to California, stuffed in a toothpaste tube, to help Olenicoff conceal $200 million in assets on which he had been evading U.S. taxes. Birkenfeld continued to advise Olenicoff even while he was giving information to the US Department of Justice, a fact which worked against him in the legal battle for his IRS reward.

Friday’s talk was organised by the Chamber of Advocates. This website has learned that the president of the Chamber, George Hyzler, who gave a brief introductory speech, is Birkenfeld’s personal legal counsel on matters related to his residency in Malta. Hyzler said in his introduction that Birkenfeld blew the whistle on UBS Bank before the introduction of the law which allows the IRS to reward whistleblowers whose information leads to the collection of taxes, fines and penalties.

This is not correct. The IRS has had that facility for many years, and in 2006 the law was actually strengthened to give higher incentives to report, and bigger rewards – of 30% of the full amount collected by the IRS in taxes, fines and penalties – to whistleblowers. Bradley Birkenfeld took his information to the US Department of Justice in 2007.

Reports in the US’s most reputable newspapers show that he then demanded a reward of “billions of dollars” based on his own estimate of how much tax UBS’s American clients had evaded, and the fines and penalties to which they were liable, but had to accept $104 million based on what the IRS actually collected. This remains an enormous amount or, as the New York Times put it “more than $4,600 for every hour he spent in prison”.

Birkenfeld showed a certain degree of annoyance at last Friday’s talk that the IRS didn’t go after more people. Unfortunately he did not put this in its proper context: that the more people the IRS went after successfully, the bigger his reward would have been at 30% of the total collected.

After reading an interview with Birkenfeld this morning in The Malta Independent, in which he fails to mention that he lives in Malta, I rang him to ask when he moved to the island, whether he did so for tax purposes, and if he is here with a view to buying Maltese citizenship.

Birkenfeld responded that he moved to Malta last year (failing to point out that he was not permitted to leave the US before that because of the conditions of his supervised release from prison), that he is “not buying a passport”, and that as a US citizen he has to pay tax in the US wherever he lives in the world. The situation, however, is not so clear-cut since Malta signed a double taxation treaty with the United States, which came into effect in 2010.

When asked why he moved to Malta – rather than, say, the far more beautiful and expansive south of France, where the climate is identical – if not for tax reasons or to buy citizenship, Birkenfeld said: “It’s warm, I like it, and I have friends here.” He did not explain further.

A criminal record is supposed to be a disqualifying factor for the purchase of Maltese citizenship, but there is no scrutiny or transparency about the system.

Birkenfeld was sentenced to 40 months but was released in August 2012 after 30 months on three-year “supervised release” or parole, during which he had to wear an electronic ankle-tag and was not permitted to leave the country before November 2015. In 2014 he filed for early release from parole on the basis that he wanted to “return to Europe to rebuild his professional life”, but was unsuccessful.

The fact that Birkenfeld is now a resident of Malta may explain his reluctance to speak about the Panama Papers, the single greatest (anonymous) whistleblowing event in history, despite describing himself as a campaigner for whistleblowers and giving a talk about the importance whistleblowing. He did not mention the subject at all at his well-attended talk on Friday.

In this morning’s interview in The Malta Independent, he was asked whether a cabinet minister should step down following revelations like those in the Panama Papers. Birkenfeld replied: “No, you cannot have a knee-jerk reaction. You cannot react blindly. But because the individual is a public servant, you should be able to ask him or her very pointed questions. When you come under the public spotlight as a public servant, unfortunately you become exposed. If you want to run for office and represent all the Maltese people, you have to be clear and clean. Otherwise, you cannot run for office.”

Except that you can.

When news of Bradley Birkenfeld’s reward from the IRS was made public in September 2012, a month after he left prison on parole, The New York Times headlined its report: “Sometimes, crime does pay”.

In 2007, Birkenfeld divulged to the US Department of Justice the schemes that UBS in Switzerland, the bank where in worked for five years, used to encourage US citizens to dodge taxes. Two years later, UBS paid $780 million to avoid criminal prosecution and turned over to the US authorities account information on 4,500 US clients. The bank managed around $20 billion in assets for US citizens.

This led to a debate in Switzerland about the retention of banking secrecy. Laws to force the disclosure of information, when it is requested by the authorities of other states, were approved by the Swiss parliament that same year. Around 14,000 US citizens with Swiss bank accounts then joined a US tax amnesty programme.

The IRS whistleblower programme allows it to deny rewards to informants who are themselves implicated or involved in the wrong-doing they report. Federal officials urged the IRS to invoke it in response to Birkenfeld’s demands for a reward. But because he had featured on 60 Minutes and the front pages of newspapers around the world, giving him a massively high profile as a whistleblower, lawyers for the IRS worried that denying him his reward because of his complicity in the crimes he reported would scare off other potential whistleblowers, on whom Birkenfeld’s prison sentence had had a chilling effect already.

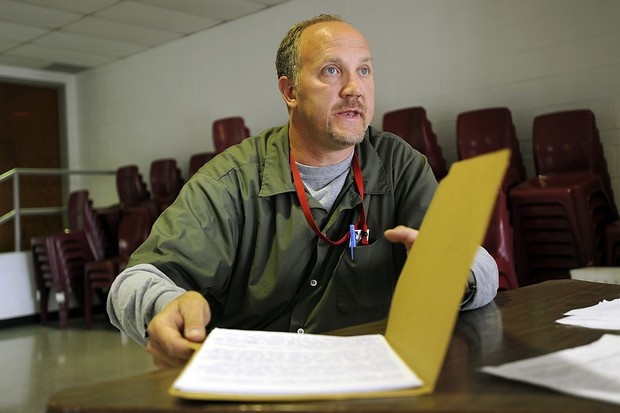

Bradley Birkenfeld while serving time in prison in the United States