When plunder becomes a way of life

“When plunder becomes a way of life for a group of men in a society, over the course of time they create for themselves a legal system that authorises it and a moral code that glorifies it.”

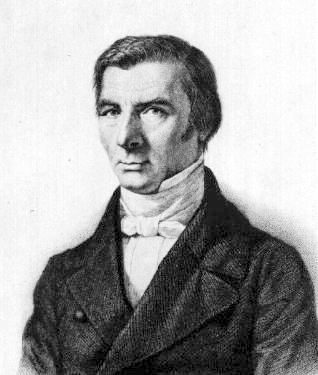

― Frédéric Bastiat

Bastiat (1801-1850) was a French classical liberal theorist, political economist, and member of the French assembly. He is noted for having developed the economic concept of opportunity cost, and for introducing the Parable of the Broken Window or The Glazier’s Fallacy, which he used to explain why destruction does not benefit the economy.

And Bastiat’s Glazier’s Fallacy is interesting, too, because it allows us to see in context what the government is doing: not just plundering, but breaking windows. Because instead of considering the good of Malta as a whole in the long term, it is working instead on the basis of how much it can do in five to ten years to pillage and to accommodate its friends, cronies and paymasters, and then it’s a matter of après moi, le deluge.

In Bastiat’s tale, a man’s son breaks a pane of glass, meaning the man will have to pay to replace it. The onlookers consider the situation and decide that the boy has actually done the community a service because his father will have to pay the glazier (window repair man) to replace the broken pane. The glazier will then presumably spend the extra money on something else, jump-starting the local economy. They therefore come to believe that breaking windows stimulates the economy.

Bastiat exposes the fallacy by explaining that in breaking the window, the man’s son has reduced his father’s disposable income. This means that his father will not be able to buy a new pair of shoes. So the broken window helps the glazier but reduces the amount spent on other goods, especially those other goods which are non-necessities and dependent on people having more disposable income to spend.

Bastiat also pointed out that replacing something that has already been bought is actually a maintenance cost, rather than a purchase of truly new goods, and maintenance doesn’t stimulate production.

In short, Bastiat suggests that destruction – and its costs – don’t benefit the economy.

The broken window fallacy also demonstrates the way the onlookers have only taken into consideration the man with the broken window and the glazier who must replace it. They have forgotten about the invisible third party, such as the shoe maker, who will be deprived of the man’s custom when the money goes on replacing window-glass instead. Their fallacy is in making a decision by looking only at the parties directly involved in the short term, when they should have been looking at all parties directly and indirectly involved in both the short and long term.