You must read this: the big front-page article in yesterday’s print edition of Sueddeutsche Zeitung

Our thanks must go to the reader who kindly agreed to patiently translate this into idiomatic English from the original German. Frederick Obermaier is one of the two journalists at the German national newspaper – the other being Bastian Obermayer – who received from an anonymous source the vast tranche of Mossack Fonseca documents that came to be known as the Panama Papers.

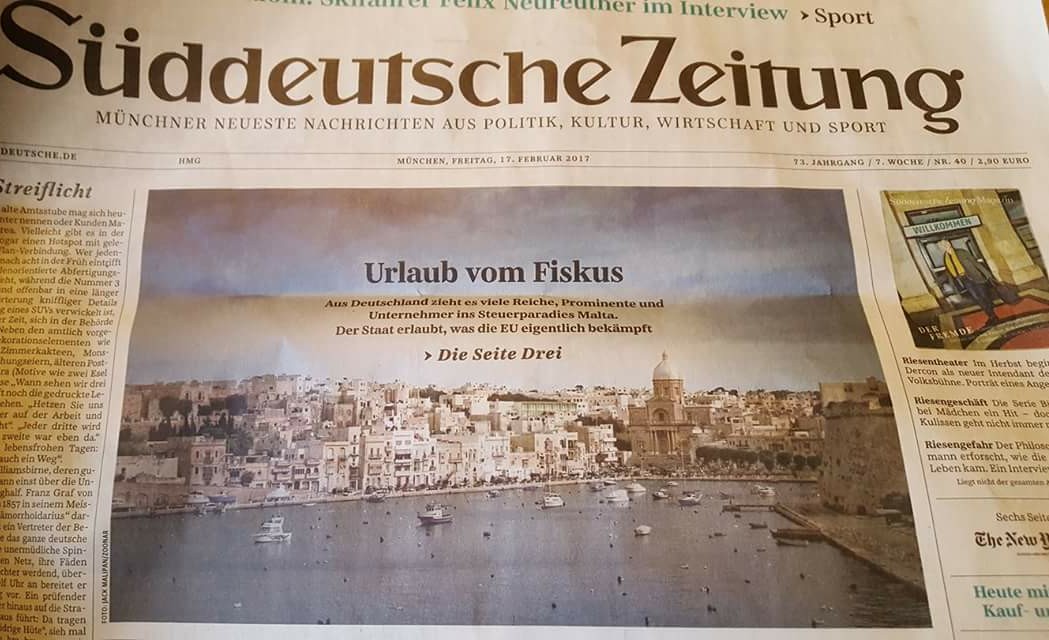

A Place in the Sun

==================

By Frederick Obermaier and Ralf Wiegand

The fact that there is a company name on the letterbox does not mean that there is a company office inside. The company name ‘Fraport’ is by the letterbox at an address in the former fishing village of St Julian’s in Malta, and beneath, ‘No junk mail’. Fraport is the company which operates Frankfurt Airport, and it is half-owned by the federal state of Hesse and the city of Frankfurt. This address even has a doorbell. But why does Fraport have a subsidiary in Malta anyway, in St Julian’s?

The woman’s voice over the intercom speaks an edgy English and sounds very far away. She refers us to Fraport’s headquarters in Frankfurt. Would she at least tell us how many people work for Fraport in St Julian’s? “Please contact the head office in Frankfurt,” she says.

It is mainly young people from Scandinavia, Italy, Spain and Germany who come to St Julian’s, to learn English. At least, that is what they tell their parents. The party zone is notorious. In the evenings, people with braces on their teeth roam the place with beer and colourful cocktails, and in the police archives, there are reports of rape and accidents. In 2011, a 14-year-old German fell from his eighth-floor hotel room balcony, and died.

The special thing about St Julian’s is that some language schools have the same address as global corporations. For example, in the Mayfair Building, which is not far from the nightlife centre of Paceville, English is taught on the ground floor. On the fourth floor, according to doorbell panel, Puma and the German fertiliser manufacturer K + S, have an address. One floor above, there is a name-plate for Sixt Financial Services. The company shares a mailbox with Lufthansa Malta Finance. A young man opens the door, with a blank expression. He disappears, returns, and hands us a pink Post-It note with “www.basf.de, www.sixt.com” written on it. And Lufthansa? He shrugs and closes the door on us.

Letterboxes – everywhere in St Julian’s there are letterboxes. There is one for Wincor Nixdorf, another German company, in the same building where Frankfurt Airport’s operating company has an address. A blonde woman wearing a fur jacket comes up to us and asks, in a stern voice, “Is there a problem?”. “You can look for those companies as long as you want to,” she says, “but they have no office in this building.” So why the letterbox, name-plate and doorbell? The woman turns away, saying she has to give her husband a quick call. Then she walks round the corner and does not come back.

Malta is the subject of hot discussion at present. The smallest country in the European Union currently holds the EU Council Presidency. Yes, it is small, but even in terms of the German standard for smallness, the Saarland, Malta is tiny. One-eighth the size of Saarland, and with half the number of inhabitants. That means you must think of something to make yourself stand out. Malta has come up with something.

The Greens in the European Parliament recently asked, as they build a report: “Is Malta a tax haven?”. The answer was yes, a tax haven right within the European Union.

Since then, Malta has been discussing the issue. Newspapers carry opinion columns on the subject. There are surveys among experts. Since 2013, the Social Democrats of the Labour Party have governed, and before that, the Nationalist Party was at the helm. Both like to accuse each other of all sorts of things, including the moral decay in Maltese politics. But on the subject of taxes, they stick together. There are no other political parties in parliament.

Owning a yacht here is nice and also very practical: you can save on taxes

Malta operates on a system which the European Union, especially since the revelations of the Luxembourg Leaks and the Panama Papers, has announced it wants to fight against. Multinational companies are passing on profits to their Maltese subsidiaries, which then pretend to be doing business on the Mediterranean island. But in fact, all they do there is pay less tax (‘letterbox companies’).

According to calculations by the newspaper Malta Today, those European member states in which the profits were really generated lose 3.5 to 4 billion euros a year in taxes because of this system. In Malta, company tax is 35 per cent, but foreign business owners can recover more than 80 per cent of that from the Inland Revenue Department.

For the rich, Malta offers the largest shipping register in Europe – not because it has the most beautiful marinas, but because the owner of a yacht can save on taxes. It is, so to speak, the perfect combination of pleasure and benefit. Although in Malta the purchase of yachts is subject to sales tax, this can be reduced to a small amount. After all, the “unique tax model”, which lawyers there speak of, makes it possible for people to lease their own yachts to themselves. The 18% tax on yachts is reduced to as low as 5.4 per cent, the Maltese assuming that they will be used mainly outside European territory. The savings can be up to 100,000 euros.

Welcome to Malta! Or as a company cheers: “Tax-haven Malta – Vacation from the tax authority.”

Many Germans like to take a bit of tax-vacation in Malta. In the Maltese company register you can only search by company name, not by the names of directors and shareholders. The Süddeutsche Zeitung, WDR and NDR have now also been able to search for personal names by means of leaked documents. Hidden at times by cryptic company names are German celebrities, large industrialists and billionaire heirs. The information that up to September of last year there were 1,616 Maltese companies with German shareholders can be obtained officially from the Maltese authorities on request, against a fee of 25 euros.

It can be inferred from the data provided by the Federal Ministry of Finance that only a fraction of these are known to the German authorities. Since 2010 only 266 German people have disclosed their Maltese companies to the German tax department. So there are 1,616 shareholders but only 266 declarations. Why is there no official communication about this between Berlin and Valletta? “Tax administration is fundamentally the responsibility of each country,” explains a government minister. He could not speak for Germany.

Unconditional discretion and sedated bureaucracy: that is what protects the very special holiday paradises like Malta. In an office building on the exit road from Valletta, there is Deloitte, one of the world’s most important accounting firms. The same address is also used by Ganesha Yachting Ltd, which is registered in Peter-Alexander Wacker’s name, the chairman of the supervisory board of Wacker-Chemie. The young receptionist shrugs her shoulders. “Just a moment. Please sit down.” Some phone calls later she is back. Nobody has ever heard of a Ganesha Yachting. But it’s in the Maltese company registry! “There must be a mistake.”

Even if letterbox companies do not need much – like real offices with real employees, for example – one thing they still need under Maltese law is a valid registered address.

Ganesha Yachting is just one of hundreds of Maltese companies which have German shareholders. Among them are operators of betting portals, suspected fraudsters, and also some unscrupulous celebrities, who have registered their boats there or apparently planned to do that. Many are likely to have relied on the typical promise of tax havens: low or no taxes, and your identity is as secure as your money. After all, who is expecting his discreetly registered company to become public overnight?

A well-known German television presenter, for example, owns a Maltese company – but that is, according to his lawyer’s communications with us, his private business and no one else’s. The television presenter, in any case, is “indisputably within the law.” There is no indication, in the two-page letter from his lawyer, whether the prominent client has declared his Maltese company to the German authorities.

Discretion is everything in this game, it is one of the basic techniques

Carsten Maschmeyer has often been on television lately. He is a friend of Schröder and Ferres’s husband. In The Lion’s Den he cast young entrepreneurs for Vox. It is also about getting a new image, Maschmeyer said in interviews, that is different to his image as one of Germany’s most controversial entrepreneurs. Maschmeyer confirms that he has temporarily owned as many as three Maltese companies to operate a yacht. But fiscal motives played “no role” in this, his spokesman said, and Maschmeyer has declared the companies to the German tax office.

In 2013, according to the Handelsblatt, Maschmeyer – who had presumably benefited from a reduced VAT rate on his yacht in Malta – demanded a luxury tax on yachts in his own country, saying: “There should be a special high tax on luxury goods, because that would be a fair redistribution and hit the right ones.” A little later, according to the Maltese register of companies, two of his Maltese companies were dissolved. The third had already been closed.

The spectacular corruption case involving the former and current Lord Mayors of Regensburg also centres on a yacht. Both men were apparently bribed by the building contractor, Volker Tretzel, who allegedly gave the former mayor, Hans Schaidinger, a sailing yacht among other things. Was this possibly one that belonged to Tretzel’s Maltese company, Ino Marine Services?

Tretzel’s Maltese company is registered at an address in an office building right on the harbour, with a view onto shiny yachts. If you get past the grim woman at reception, you find yourself in a corridor, where there is a door to a company called Vistra, a specialist in ship registration. A friendly employee leads the way to the managing director, and before we go in, we overhear the conversation through the door. “A journalist? What, he’s already in here? Oh, no.”

“Tretzel, yes – we manage a yacht for the gentleman,” says the man in his mid-forties, later. He is aware of the fact that the German “gentleman” is currently held on remand in a German prison on bribery charges, about a yacht among other things. “Our compliance man is working on it.” Compliance men are those who keep watch during business deals that laws are adhered to, so as not to have the authorities at their necks. The managing director says he will send us more details by e-mail, which we never receive.

“Hans Schaidinger did not use this yacht or any other yacht owned by Volker Tretzel (…),” Tretzel’s lawyer replies to our questions on the matter. His client had paid “all (sales) taxes”. He did not say whether the Maltese company has been declared to the German tax authorities.

Discretion is everything in this game, it is one of the basic techniques that all players must master. And Malta has experience in the great tax charade. Only in stormy Iceland was a government similarly deeply entangled in the Panama Papers, in those revelations from the belly of a Panamanian offshore service provider. Two of the closest confidants of Prime Minister Joseph Muscat, his then health and energy minister, Konrad Mizzi, and his chief of staff, Keith Schembri, had money hidden through a web of companies in Panama and trusts in New Zealand.

In Malta it was The Scandal, in the spring of 2016. The newspapers covered it like there had never been a bigger one. Thousands of citizens demonstrated outside the Office of the Prime Minister and demanded his resignation, carrying placards with the word ‘Barra’, which means ‘Out’. Muscat’s government survived a vote of confidence, but in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, Malta has fallen 10 places. It is now ranked in 47th place, its worst ever.

Anyone who, in Malta and to the Maltese, describes the country for what it is – a tax haven – shouldn’t expect applause. When Malta Today published its figures, it received harsh insults. This is a “stupid and harmful article”, one person commented on Facebook. Why would the newspaper intentionally harm the national interest? The economy of the country would collapse without this tax system. The writer of the article was pilloried, described as having “his pants down”. Another reader was puzzled: “Malta Today wtf! Are you out of your mind??”

Malta obviously lives well off the few taxes that it levies, like those of Ralf Schumacher, for example. The racing driver’s lawyer tells us that he did not set up the Maltese company which he owns, which is called Sea Dream Ltd, but bought it as the means of acquiring the yacht it owned. He bought the yacht’s Maltese holding company to buy the yacht. Schumacher undertook to continue the leasing relationship begun by the seller. And what about the savings on taxes? Life is hard.

Günter Herz, an ex-co-owner of Tchibo, is one of the richest Germans, and he has a Maltese company which owns a boat. It was set up in 2004 and is called All Smoke Yachts I Ltd.

And Peter-Alexander Wacker, who owns the letterbox company without a letterbox? He, too, has his lawyer write to us, a letter which cannot be quoted in whole or in part. He leaves unanswered the question of why no one at his company address knows of his company’s existence. It is the mystery of Malta.

Even a Hesse state-owned company is involved – for the purpose of “optimising the control position”

Malta is the most densely populated country in Europe. Most families have two cars that seem to be all on the road to Valletta at the same time. Physical distances on the island are short, but travel time is long. Two-thirds of the 430,000 islanders live in or around the capital. Valletta, a world heritage site, is an imposing fortress built from light coloured sandstone, perched on a peninsula between fjord-like sea arms. The crusaders had once erected them as a bulwark against the Ottomans. Today, signs with the wreath of twelve stars on many buildings point to EU grants. Our Lady of Victories Church, for example, Valletta’s first building: it has been restored with EU funds. Or Fort St. Elmo, the northern fortification of Valletta: it has been rehabilitated with EU funds. Also the Barrakka lift, which takes you in only 28 seconds from the Grand Harbour to the old town: co-financed by the EU.

It is a peculiar challenge when the EU subsidises and promotes a tax haven which deprives its fellow member states of tax revenue. More so when a German state-owned company like Fraport Malta Business Services Ltd, uses measures to avoid paying tax in Germany itself, using a letterbox company in Malta, that has a name-plate and a doorbell, but no employees. The Ministry of Finance in Hesse said in 2013, in response to a question from the Greens, that the Maltese company is there to “optimise our tax position”, because corporation tax can be minimised in Malta. When even German state-owned companies are involved in this, it is possible to understand why a loophole like Malta is so difficult to close.

Since 2014, the Valletta government has even been offering EU passports for sale. Anyone who invests about one million euros in the island state can become a citizen – and does not even have to live there. The European Parliament thundered that EU citizenship should not be “for sale at any price”, but it could not do anything about it. Citizenship is the responsibility of individual member states. Like all EU citizens, those who hold a Maltese passport may travel, reside and work freely in the Schengen area, a freedom of movement which can also be helpful in the circumvention of sanctions or anti-money-laundering laws. Meanwhile, through this “individual investor programme”, which is one of the favourite projects of Prime Minister Joseph Muscat, Malta has welcomed hundreds of new citizens, most of them from Russia, China and the Middle East.

Obviously, it is not only economic refugees who enter the EU via the Mediterranean. The rich also travel – however, not by dinghy.

Collaboration: Catharina Felke