The false emotion of pathological egocentricity

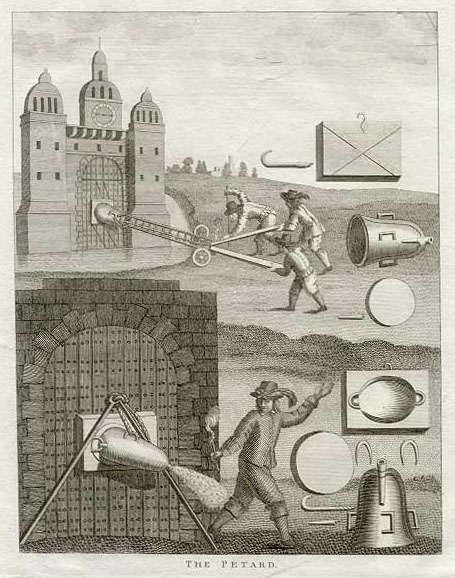

“I was inspired to write this article by a man who years ago at a village feast saw a young boy he barely knew parading an unignited petard which he was banging against a wall.

The man lunged towards him, yelling at the boy to stop what he was doing because the firework may go off. He managed to seize the petard. As soon as he did so, it ignited. The boy was unhurt. The man lost part of his right palm.

Had the man failed to act, the young boy would have lost his arm, his eyes, possibly his life.

During his long term in hospital, the man, a humble salesman who earned a living from writing and carrying boxes, learnt to write with his left hand and how to handle things with his disabled body part. Years of practice led him to re-learn writing with his right hand.

He never complained, always feeling it was his duty to save the young boy, whom he did not know, and he would undoubtedly do the same again. That man was my father.”

This was the grand finale of an article published under the name of opposition leader Joseph Muscat, in The Sunday Times, 12 September, after it was revealed that his father is one of Malta’s leading merchants in the fireworks chemicals trade, a fact not mentioned in the article, which instead uses wildly inaccurate words like ‘disabled’ to trade on false emotion.

Do you know how it is when you’re talking to somebody and picking up signals that they’re not being quite straight with you, that they’re hiding or twisting something or manipulating the facts, and yet on the face of it everything seems in order and you have no rational reason to doubt what’s being said, so you dismiss your inner disquiet as irrational and ignore it?

Then you find out that you shouldn’t have ignored it at all, that your inner disquiet was bang on the money.

That’s how I felt when I read the article which somebody had written for Joseph Muscat to have published under his name in The Sunday Times the day before yesterday.

There was something not quite right about it.

That it was laden with half-truths and omissions about what his father does for a living (profit from fireworks chemicals) goes without saying.

I can’t understand why his advisers thought it made good sense to leave out that salient information, unless they commissioned the piece and had it written before the Sunday papers began ringing the telephone number I published to get hold of Mr Muscat senior for interviews (he referred them to his lawyer, which says a lot).

I’m trying to work out what the signals are that raise the alarm for me about the truth, honesty and sincerity of that newspaper article, and which call all three into doubt.

Let’s leave aside the fact that I am instantly wary of the sincerity of a man who describes his wife’s vaginal bleeding to a prime-time television audience, for political advantage (he did that on Sunday night).

When a major life event occurs that shapes our way of looking at things, and we write or speak about how it changed or influenced us, we put that life event at the beginning of our narrative and not at the end.

This is not just in the interests of good story-telling (the hook should come at the start for maximum impact and to reel in readers and listeners), but also because of the logical progression of ideas. This is what happened. This is how it changed the way I see things.

It is also our psychology which makes us lead our narrative with the event which influenced us. Because it looms large in our consciousness, because it is so important in the story of our lives, we begin with it. Not only do we begin with it, but we also give the date, because that date is scored into our memory and plays an essential role in the narrative.

So a piece might begin ‘I lost my mother on 28 May 1980 when I was six years old’ or ‘My parents died in a car crash in June 1970 when I was 10’ or ‘My daughter died of a drug overdose when she was 20.’ You get the idea. That’s the usual way of writing these things.

You know immediately that this is the life event that looms largest in the writer’s consciousness, causing him to divide his life into Before and After.

You don’t get that impression when reading Joseph Muscat’s description of how his father was injured when taking a petard off a boy who risked blowing himself up.

The description is distant, curiously dispassionate and uninvolved. The attempted emotion rings false. And it comes right at the end of the article, which conveys the message that this wasn’t really that important to him but he thinks he should mention it so that we can feel for him and he can gain some public relations points.

Of course, the curious sense of distance, false emotion and lack of involvement might just be because he isn’t the one who wrote that piece and the person who did write it lacks the necessary skills of empathy and thinking yourself ‘into’ the individual you are ghosting for.

But then when Joseph Muscat read it before allowing it to be released to The Sunday Times under his name – I am assuming here that he did read it first – it should have rung as false to him as it did to me.

When you use an event, which is supposed to have caused you great and life-changing sorrow, as the supposed grand finale of a political piece which serves as the build-up, you come across as insincere, as using that event to manipulate the situation or public perception of you. And people who read it know instinctively at some deep level – those irrational alarm bells ringing at the backs of our minds – that it really wasn’t that important to you at all and that the person yoo care most about is yourself.

When there has been real trauma, however distant in time, those who experienced it are unable to speak of it because they fear the raw emotion that might spill forth or the pain that might well up again and take over. If they do speak of it, it is with tightly controlled emotion and just the barest of facts, or with that raw and honest emotion that is unmistakable, but which frightens others because they can’t handle it and they find the public display of private pain deeply embarrassing.

Those with painful memories do not use them cynically to gain advantage. The presence of cynical manipulation is in itself indicative of the absence of real emotion.

But aside from Muscat’s insincere emotions, there are questions to be asked, more properly, about the facts of the event he describes.

When did it happen?

Who was the boy?

What exactly happened with that petard? If it had exploded, as Muscat seeks to give the impression it did through the ‘cunning’ use of the word ‘ignited’, his father’s injuries wouldn’t have been only to ‘a bit of his right palm’. He would be dead, blind, missing most of his torso or his limbs.

Why would he have been kept in hospital for a ‘long term’ because of an injury to the palm of his right hand? Outpatient treatment, of course – but actually in hospital? I don’t think so. It just sounds more dramatic to say that your father was hospitalised for ‘a long term’ because he saved a boy. It heightens the sense of heroism in a way that saying ‘my father’s right palm was injured and he had to go to outpatients for months afterward’ does not.

As for the reference to ‘a humble salesman who made his living by writing and carrying boxes’, the inference being that it was a great tragedy for him to lose, however briefly, the use of his right hand, I think it was most unwise. Muscat’s ghost-writer should have carried on with the narrative all the way through to its happy ending, where the humble box-carrying salesman, unhindered by his right palm, goes on to become a rich merchant trading in chemicals that other people use to blow themselves up, using the profits to spoil his only child in such a way that, at 36 and with a wife and two children, he continues to manifest the signs of retarded emotional development and a magnificent egocentricity that is quite fascinating to watch.

14 Comments Comment

Leave a Comment

It is very worrying that such a person is at the helm of the second largest politial party in Malta.

The narrative is similar to the one by Marisa Micallef about the Red Blue Prince, published by The Times about a year ago. This could be the reason for the lack of emotion you mention.

Ara kemm se nfaqqghu murtali meta Malta ikollha il-Presidenza tal-Ewropa fit-2017. Dakinhar, Malta tkun il-Leader tal-Ewropa, u Joseph Muscat ikun il-Leader ta’ Malta.

U l-Ewropa hija l-Leader tad-Dinja. Ergo: Joseph Muscat huwa l-Leader tad-Dinja. U missieru se jiehu l-kuntratti kollha ghall-murtali li se jidhru fil-galassja kollha.

U minflok il-kaxxa infernali, ikollna Big Bang universali…

Ezatt. If his ghostwriter wanted to learn the art of good prose, he should read your erticles. Wow !!

I’m not referring to the theme per se, but the style in itself reminds you of the great Roman orators, or Chaucer’s Ars Praedicandi…….

[Daphne – One rule of good writing is never to use clunking sarcasm. It shows a severe lack of skill. To be effective, sarcasm must be very subtle. Then it’s called wit.]

Nice try, Joseph.

Not related to the topic. Maltastar gives the ’emeritus’ treatment to Clinton:

“American President emeritus Bill Clinton ..”

Why don’t you give him some ‘privat tal-inglish’ it’s only down the road after all?

The devil accusing the sinner of a sin! As much as you may be right in pointing out how uncontextual Muscat’s article is, I also think that leaving out relevant bits and pieces out one’s articles is a sport you kick everyone’s ass at. I know we’ve been through this road before but I couldn’t help not remarking it again.

[Daphne – The day I write an article about something in which I have a vested interest and from which my family makes its money, while trying my best to hide that fact, let me know.]

You are well aware that ‘interest’ is a vague and subjective word and limiting it to money is a cheap way to try to win an argument. Fundamentalists like you don’t do the things they do for money.

Even most of those crazy talibans don’t have any financial interest in their so called causes but that doesn’t stop them from persecuting any so-called infidels who get in their way, does it?

Again, as an extremist, your arguments, irrespective of how creative and well written they are, will always be destined to fail due to their constant lack of context, balance and journalistic objectivity.

[Daphne – Read Mark-Anthony Falzon on the role of a columnist, in The Sunday Times last Sunday. I’m tempted to call you a cretin, but I’ll resist.]

If there was any further proof of his cynicism, Joseph Muscat couldn’t be fagged to attend the first funeral of the victims today. Maybe he’ll show up tomorrow for the joint funeral: more cameras there.

Maybe he is still limping. The Gozo ferry is hardly a cruise ship.

Forsi d-deni jaghmillu l-bahar u ghal-gita mar b’sagrificcju kbir biex ikollu naqa’ femili tajm.

Arah jinnegozja kif kien jaghmel Mintoff!

Mintoff kien jighijihom, dan jighijja qabel jibda.

Immagina lil Gaddafi jistenna ‘l Joseph jaghmel il-bjutij slijp.